Cry Freedom 1322r

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report 2z6p3t

Overview 5o1f4z

& View Cry Freedom as PDF for free.

More details 6z3438

- Words: 3,485

- Pages: 6

Cry Freedom Cry Freedom is a 1987 British drama film directed by Richard Attenborough, set in the late 1970s, during the apartheid era of South Africa. The screenplay was written by John Briley based on a pair of books by journalist Donald Woods. The film centres on the real-life events involving black activist Steve Biko and his friend Donald Woods, who initially finds him destructive, and attempts to understand his way of life. Denzel Washington stars as Biko, while actor Kevin Kline portrays Woods. Cry Freedom delves into the ideas of discrimination, political corruption, and the repercussions of violence.

derstand Biko’s point of view, a friendship slowly develops between them. After being arrested for speaking at a gathering of black South Africans outside of his banishment zone, Biko is arrested and interrogated by South African security forces. Following this, he is brought to court in order to explain his message directed toward the South African government. After he speaks eloquently in court and advocates non-violence, the security officers who interrogated him visit his church and vandalize the property. Woods assures Biko that he will meet with a government official to discuss the matter. Woods then meets with Jimmy Kruger (John Thaw), the South African Minister of Justice in his house in Pretoria in an attempt to prevent further abuse by the security force. Kruger first expresses discontent over the actions of security force, however Woods is later harassed by security forces at his home. The security men that harass Woods insinuate that their orders to visit Woods came directly from Kruger.

The film was primarily shot on location in Zimbabwe due to political turmoil in South Africa at the time of production. As a film showing mostly in limited cinematic release, it was nominated for multiple awards, including Academy Award nominations for Best Actor in a ing Role, Best Original Score, and Best Original Song. It also won a number of awards including those from the Berlin International Film Festival and the British Academy Film Awards. Later, Biko decides to travel to Cape Town to speak at A t collective effort to commit to the film’s produc- a student-run meeting. En route, security forces stop his tion was made by Universal Pictures and Marble Arch car and arrest him. He is held in harsh conditions and Productions. It was commercially distributed by Univer- beaten, causing a severe brain-injury. A doctor recomsal Pictures theatrically, and by MCA Home Video for mends consulting a nearby specialist in order to best treat home media. Cry Freedom premiered in theaters nation- his injuries, but the police refuse due to fear that he might wide in the United States on 6 November 1987 grossing escape. (This would have been nearly impossible, consid$5,899,797 in domestic ticket receipts. The film was at ering that the severity of his injuries left him with nearly its widest release showing in 479 theaters nationwide. It complete inability to move on his own.) The security was generally met with positive critical reviews before its forces instead decide to take him to a prison hospital in Pretoria, around 700 miles away from Cape Town. He initial screening in cinemas. is thrown into the back of a prison van and driven on a bumpy road, aggravating his brain injury and resulting in his death. 1 Plot Woods then works to expose the police’s complicity in Biko’s death. He attempts to expose photographs of Biko’s body that contradicted police reports that he died of a hunger strike, but he is prevented just before boarding a plane to leave and informed that he is now banned, therefore not able to leave the country. Woods and his family are targeted in a campaign of harassment by the security police. He later decides to seek asylum in England to expose the corrupt and racist nature of the South African authorities. After a long trek, Woods is eventually able to escape to the country of Lesotho, disguised as a priest. His wife Wendy (Penelope Wilton) and their family later him, and are flown to Botswana with the aid of Bruce Haigh (John Hargreaves), a controversial Australian diplomat who uses his diplomatic immunity to help them. In the film, however, Hargreaves’ character is

Following a news story depicting the demolition of a slum in East London, South Africa, journalist Donald Woods (Kevin Kline) seeks more information about the incident and ventures off to meet black activist Steve Biko (Denzel Washington). Biko has been officially banned by the South African government and is not permitted to leave his defined banning area at King William’s Town. Woods is formally against Biko’s banning, but remains critical of his political views. Biko invites Woods to visit a black township to see the impoverished conditions and to witness the effect of the government-imposed restrictions, which make up the apartheid system. Woods begins to agree with Biko’s desire for a South Africa where blacks have the same opportunities and freedoms as those enjoyed by the white population. As Woods comes to un1

2

3

PRODUCTION

an Australian journalist.

• John Thaw - Jimmy Kruger, Minister of Justice

The film’s epilogue displays a graphic detailing a long list of anti-apartheid activists (including Biko), who died under suspicious circumstances while imprisoned by the government. Contrary to popular belief, the listing’s dates in the graphic actually stopped in June 1987, a few months before the film’s release, as the Apartheid government stopped releasing the increasingly obviously false “official explanations” for deaths in custody.

• Michael Turner - Judge Boshoff

2

Cast • Denzel Washington - Stephen Biko • Juanita Waterman - Ntsiki Biko, Steve Biko’s wife • Kevin Kline - Donald Woods

• Graeme Taylor - Dillon Woods, eldest son of Woods family • Kate Hardie - Jane Woods, eldest daughter of Woods family • Adam Stuart Walker - Duncan Woods, son of Donald and Wendy Woods • Hamish Stuart Walker - Gavin Woods, son of Donald and Wendy Woods • Spring Stuart Walker - Mary Woods, daughter of Donald and Wendy Woods • Munyaradzi Kanaventi - Samora Biko • George Lovell - Nkosinathi Biko

• Penelope Wilton - Wendy Woods • Kevin McNally - Ken, photographer at Daily Dispatch

3 Production

• Timothy West - Capt. de Wet

3.1 Development

• John Hargreaves - Bruce Haigh • Miles Anderson - Lemick • Morgan Sheppard as Policeman • Mawa Makondo - Jason • Wabei Slyolwe - Tenjy • Tommy Buson - Tami • Jim Findley - Peter Jones • Alec McCowen - British Acting High Commissioner • Zakes Mokae - Father Kani • John Matshikiza - Mapetla • Ian Richardson - State Prosecutor • • • • • • • •

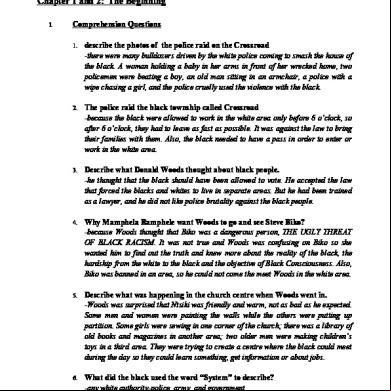

Racial-demographic map of South Africa in the late 1970s.

The premise of Cry Freedom is based on the true story of Steve Biko, the charismatic South African Black Josette Simon - Dr. Mamphela Ramphele Consciousness Movement leader who attempts to bring Louis Mahoney - Lesotho Government Official awareness to the injustice of Apartheid; and Donald Woods, the liberal white editor of the Daily Dispatch Joseph Marcell - Moses, Lesotho postal worker newspaper who struggles to do the same after Biko is Sophie Mgcina - Evalina, Wood family’s domestic murdered. In 1972, Biko was one of the founders of the Black People’s Convention working on social upliftmaid ment projects around Durban.[2] The BPC brought toJohn Paul - Wendy’s Stepfather gether almost 70 different black consciousness groups and associations, such as the South African Student’s Gwen Watford - Wendy’s Mother Movement (SASM), which played a significant role in Nick Tate - Ritchie private aviator who took Woods the 1976 uprisings, and the Black Workers Project which ed black workers whose unions were not recogfamily from Lesotho to Botswana nized under the Apartheid regime.[2] Biko’s political acGarrick Hagon - McElrea, private aviator tivities eventually drew the attention of the South African

4.1

Critical response

government which often harassed, arrested, and detained him. These situations resulted in him being banned in 1973.[3] The banning restricted Biko from talking to more than one person a time, in an attempt to suppress the rising anti-apartheid political movement. Following a violation of his banning, Biko was arrested and later killed while in police custody. The circumstances leading to Biko’s death caused worldwide anger, as he became a martyr and symbol of black resistance.[2] As a result, the South African government banned a number of individuals (including Donald Woods) and organizations, especially those closely associated with Biko.[2] The United Nations Security Council responded swiftly to the killing by later imposing an arms embargo against South Africa.[2] After a period of routine harassment against his family by the authorities, as well as fearing for his life,[4] Woods fled the country after being placed under house arrest by the South African government.[4] Woods later wrote a book in 1978 entitled: Biko, exposing police complicity in his death.[3] That book, along with Woods’ autobiography Asking For Trouble, both being published in the UK, became the basis for the film.[3]

3.2

Filming

Principal filming took place primarily in the country of Zimbabwe due to the tense political situation in South Africa at the time of shooting. Other filming locations included Kenya, as well as film studios in Shepperton and Middlesex, England.[5] The film includes a dramatized depiction of the Soweto uprising which occurred on 16 June 1976. Indiscriminate firing by police, killed and injured hundreds of African school children during a protest march.[3]

3.3

Soundtrack

The original motion picture soundtrack for Cry Freedom was released by MCA Records on 25 October 1990.[6] It features songs composed by veteran musicians George Fenton, Jonas Gwangwa and Thuli Dumakude. At Biko’s funeral they sing the hymn Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika. Jonathan Bates edited the film’s music.[7]

4 4.1

Reception Critical response

Among mainstream critics in the U.S., the film received mostly positive reviews. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 81% of 21 sampled critics gave the film a positive review, with an average score of 6.4 out of 10.[8] Rita Kempley, writing in The Washington Post, said actor Washington gave a “zealous, Oscar-caliber performance as this African messiah, who was recognized as

3 one of South Africa’s major political voices when he was only 25.”[10] Also writing for The Washington Post, Desson Howe thought the film “could have reached further” and felt the story centering around Wood’s character was “its major flaw”. He saw director Attenborough’s aims as “more academic and political than dramatic”. Overall, he expressed his disappointment by exclaiming, “In a country busier than Chile with oppression, violence and subjugation, the story of Woods’ slow awakening is certainly not the most exciting, or revealing.”[11] Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times offered a mixed review calling it a “sincere and valuable movie” while also exclaiming, “Interesting things were happening, the performances were good and it is always absorbing to see how other people live.” But on a negative front, he noted how the film “promises to be an honest of the turmoil in South Africa but turns into a routine cliff-hanger about the editor’s flight across the border. It’s sort of a liberal yuppie version of that Disney movie where the brave East German family builds a hot-air balloon and floats to freedom.”[12] Janet Maslin writing in The New York Times saw the film as “bewildering at some points and ineffectual at others” but pointed out that “it isn't dull. Its frankly grandiose style is transporting in its way, as is the story itself, even in this watered-down form.” She also complimented the African scenery, noting that "Cry Freedom can also be ired for Ronnie Taylor’s picturesque cinematography”.[9] The Variety Staff, felt Washington did “a remarkable job of transforming himself into the articulate and mesmerizing black nationalist leader, whose refusal to keep silent led to his death in police custody and a subsequent coverup.” On Kline’s performance, they noticed how his “low-key screen presence served him well in his portrayal of the strong-willed but even-tempered journalist.”[13] Film critic Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film a thumbs up review calling it “fresh” and a “solid adventure” while commenting “its images do remain in the mind ... I ire this film very much.” He thought both Washington and Klines’ portrayals were “effective” and “quite good”.[14] Similarly, Michael Price writing in the Fort Worth Press viewed Cry Freedom as often “harrowing and naturalistic but ultimately selfimportant in its indictment of police-state politics.”[15] Mark Salisbury of TimeOut boasted on the film’s merits by declaring the lead acting to be “excellent” and the crowd scenes “astonishing”, while equally observing how the climax was “truly nerve-wracking”. He called it “an implacable work of authority and comion, Cry Freedom is political cinema at its best.”[16] James Sanford however, writing for the Kalamazoo Gazette, did not appreciate the film’s enduring qualities, calling it “a Hollywood whitewashing of a potentially explosive story.”[17] Rating the film with 3 Stars, critic Leonard Maltin wrote that the film was a “Sweeping and comionate film”. He did however note that the film “loses momentum as it spends too much time on Kline and his family’s escape

4

6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

from South Africa”. But in positive followup, he pointed out that it “cannily injects flashbacks of Biko to steer it back on course.”[18]

4.2

Accolades

The film was nominated and won several awards in 1987– 88.[19][20] Among awards won were from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Berlin International Film Festival and the Political Film Society.

4.3

Box office

6 Bibliography • Biko, Steve (1979). Steve Biko: Black Consciousness in South Africa; Biko’s Last Public Statement and Political Testament. Random House. ISBN 978-0394-72739-4. • Biko, Steve (2002). I Write What I Like: Selected Writings. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780-226-04897-0. • Clarke, Anthony J.; Fiddes, Paul S., eds. (2005). Flickering Images: Theology and Film in Dialogue. Regent’s Study Guides 12. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing. ISBN 1-57312-458-3.

The film premiered in cinemas on 6 November 1987 in limited release throughout the U.S.. During its opening weekend, the film opened in a distant 19th place and grossed $318,723 in business showing at 27 theaters.[28] The film Fatal Attraction opened in first place with $7,089,680 screening at 1,351 theaters.[1] The film’s revenue dropped by 10.6% in its second week of release, earning $284,853. For that particular weekend, the film fell to 25th place showing in 19 theaters. The film The Running Man, unseated Fatal Attraction to open in first place with $8,117,465 in box office revenue showing at 1,692 theaters.[1][28]

• Goodwin, June (1995). Heart of Whiteness: Afrikaners Face Black Rule In the New South Africa. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-81365-3.

Cry Freedom had one week in wider release beginning with the 19–21 February weekend in 1988.[1] The film opened in 14th place showing at 479 theaters grossing $802,235 in box office business. The film went on to top out domestically at $5,899,797 in total ticket sales through an 4-week theatrical run.[1] For 1987 as a whole, the film would cumulatively rank at a box office performance position of 103.[1]

• Magaziner, Daniel (2010). The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968-1977. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-08214-1918-2.

4.4

Home media

Following its cinematic release in theaters, the film was released in VHS video format on 5 May 1998.[29] The Region 1 Code widescreen edition of the film was released on DVD in the United States on 23 February 1999. Special features for the DVD include; production notes, cast and filmmakers bios, film highlights, web links, and the theatrical trailer.[30] Currently, there is no scheduled release date set for a future Blu-ray Disc version of the film, although it is available in other media formats such as Video on demand.[31]

5

See also • White savior narrative in film • 1987 in film

• Harlan, Judith (2000). Mamphela Ramphele. The Feminist Press at CUNY. ISBN 978-1-55861-2266. • Juckes, Tim (1995). Opposition in South Africa: The Leadership of Z. K. Matthews, Nelson Mandela, and Stephen Biko. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-27594811-5.

• Malan, Rian (2000). My Traitor’s Heart: A South African Exile Returns to Face His Country, His Tribe, and His Conscience. Grove Press. ISBN 978-08021-3684-8. • Omand, Roger (1989). Steve Biko and Apartheid (People & Issues). Hamish Hamilton Limited. ISBN 978-0-241-12640-0. • Paul, Samuel (2009). The Ubuntu God: Deconstructing a South African Narrative of Oppression. Pickwick Publications. ISBN 978-1-55635-510-3. • Pityana, Barney (1992). Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko & Black Consciousness. D. Philip. ISBN 978-1-85649-047-4. • Price, Linda (1992). Steve Biko (They Fought for Freedom). Maskew Miller Longman. ISBN 978-0636-01660-6. • Tutu, Desmond (1996). The Rainbow People of God. Image. ISBN 978-0-385-48374-2. • Van Wyk, Chris (2007). We Write What We Like: Celebrating Steve Biko. Wits University Press. ISBN 978-1-86814-464-8.

5 • Wa Thingo, Ngugi (2009). Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance. Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00946-6. • Wiwa, Ken (2001). In the Shadow of a Saint: A Son’s Journey to Understand His Father’s Legacy. Steerforth. ISBN 978-1-58642-025-3. • Woods, Donald (2004). Rainbow Nation Revisited: South Africa’s Decade of Democracy. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-233-00052-7.

7

[19] “Cry Freedom: Awards & Nominations”. MSN Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [20] “Cry Freedom (1987)". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 201006-15. [21] “Nominees & Winners for the 60th Academy Awards”. Oscars.org. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [22] “Cry Freedom”. BAFTA.org. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [23] “Cry Freedom”. Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [24] “Cry Freedom”. GoldenGlobes.org. Retrieved 2010-0615.

References

[1] “Cry Freedom”. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-0615. [2] “Stephen Bantu (Steve) Biko”. About.com. Retrieved 2010-06-20. [3] “Stephen Bantu Biko”. South African History Online. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[25] “31st Annual Grammy Award Highlights”. Grammy.com. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [26] “Awards for 1987”. nbrmp.org. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [27] “Previous Winners”. Political Film Society. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [28] “Cry Freedom”. The Numbers. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[4] 1978: Newspaper editor flees South Africa. BBC. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

[29] “Cry Freedom VHS Format”. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[5] Attenborough, Richard (Director). (1987). Cry Freedom [Motion picture]. United States: Universal Pictures.

[30] “Cry Freedom: On DVD”. MSN Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[6] “Cry Freedom: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack”. Amazon. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[31] “Cry Freedom: VOD Format”. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

[7] “Cry Freedom”. Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [8] Cry Freedom (1987). Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [9] Maslin, Janet (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [10] Kempley, Rita (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [11] Howe, Desson (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [12] Ebert, Roger (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [13] Variety Staff (1 January 1987). Cry Freedom. Variety. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [14] Siskel, Gene (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. At the Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [15] Price, Michael (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Fort Worth Press. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [16] Salisbury, Mark (6 November 1987). TimeOut. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

Cry Freedom.

[17] Sanford, James (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Kalamazoo Gazette. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [18] Maltin, Leonard (5 August 2008). Leonard Maltin’s 2009 Movie Guide. Signet. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

8 External links • Official website • Cry Freedom at the Internet Movie Database • Cry Freedom at AllMovie • Cry Freedom at the Movie Review Query Engine • Cry Freedom at Rotten Tomatoes • Cry Freedom at Box Office Mojo • Cry Freedom film trailer at YouTube

6

9 TEXT AND IMAGE SOURCES, CONTRIBUTORS, AND LICENSES

9

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

9.1

Text

• Cry Freedom Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cry%20Freedom?oldid=638815586 Contributors: Deb, SimonP, Skysmith, Dimadick, Academic Challenger, David Gerard, Angmering, Andycjp, Lockeownzj00, Robert Brockway, OwenBlacker, Kuralyov, ScottyBoy900Q, Jayjg, Discospinster, WegianWarrior, Darwinek, Erik, Cburnett, Panchurret, Kelisi, GregorB, Rjwilmsi, Harro5, Darguz Parsilvan, MarnetteD, Andreas S., Jay-W, Gwernol, YurikBot, RussBot, Briaboru, Quentin Smith, Muntuwandi, UDScott, Catamorphism, RFBailey, Bigrich, Bibliomaniac15, SmackBot, Pgk, Michaelbeckham, Kintetsubuffalo, Jakz34, Bluebot, Zaian, Dr.Poison, JJW20084, Halaqah, Xionbox, Dl2000, Benmay, Luigibob, Aapold, Lbr123, CmdrObot, ShelfSkewed, Cydebot, Treybien, Tec15, Alaibot, Gnfnrf, NorthernThunder, BetacommandBot, Thijs!bot, Marek69, Dawkeye, ABCxyz, MegX, Joshua, Easchiff, PacificBoy, Avicennasis, Indon, Emcardi, Grushenka, Mannerheim, Blupping, MartinBot, Rhino131, Wlodzimierz, Mike.lifeguard, PythonMonty504, Jojoster, Tai kit, Themoodyblue, Crazytrucker, Sparkymeg, Philip Trueman, OldZombie, Broadbot, McM.bot, Sparkling Gray, Pällikkä, SieBot, Nubiatech, A. Carty, Aspects, Beemer69, ClueBot, The Thing That Should Not Be, Jan1nad, RossMcG, Justinmckee07, HarryKG, GDibyendu, Addbot, EjsBot, Tide rolls, Zorrobot, Luckas-bot, Yobot, AnomieBOT, Ulric1313, Materialscientist, LilHelpa, Xqbot, Tuesdaily, Ched, LucienBOT, Nakakapagpabagabag, Winterst, ScottMHoward, Cnwilliams, Hummingbird347, Nistra, EmausBot, Wikipelli, ZéroBot, Josve05a, DeWaine, SporkBot, Δ, ClueBot NG, Helpful Pixie Bot, Montalban, Katangais, MinghamSmith, Mmancino, JustBerry, Dancedom, Taylor Trescott, Vieque and Anonymous: 135

9.2

Images

• File:South_Africa_racial_map,_1979.gif Source: http://.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d1/South_Africa_racial_map% 2C_1979.gif License: Public domain Contributors: Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by :Magnus Manske using CommonsHelper. (Original text : * Site: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection: South Africa Maps Original artist: U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Original er was MaGioZal at en.wikipedia • File:Video-x-generic.svg Source: http://.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/e/e7/Video-x-generic.svg License: Public domain Contributors: ? Original artist: ? • File:Wikiquote-logo.svg Source: http://.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fa/Wikiquote-logo.svg License: Public domain Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

9.3

Content license

• Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

derstand Biko’s point of view, a friendship slowly develops between them. After being arrested for speaking at a gathering of black South Africans outside of his banishment zone, Biko is arrested and interrogated by South African security forces. Following this, he is brought to court in order to explain his message directed toward the South African government. After he speaks eloquently in court and advocates non-violence, the security officers who interrogated him visit his church and vandalize the property. Woods assures Biko that he will meet with a government official to discuss the matter. Woods then meets with Jimmy Kruger (John Thaw), the South African Minister of Justice in his house in Pretoria in an attempt to prevent further abuse by the security force. Kruger first expresses discontent over the actions of security force, however Woods is later harassed by security forces at his home. The security men that harass Woods insinuate that their orders to visit Woods came directly from Kruger.

The film was primarily shot on location in Zimbabwe due to political turmoil in South Africa at the time of production. As a film showing mostly in limited cinematic release, it was nominated for multiple awards, including Academy Award nominations for Best Actor in a ing Role, Best Original Score, and Best Original Song. It also won a number of awards including those from the Berlin International Film Festival and the British Academy Film Awards. Later, Biko decides to travel to Cape Town to speak at A t collective effort to commit to the film’s produc- a student-run meeting. En route, security forces stop his tion was made by Universal Pictures and Marble Arch car and arrest him. He is held in harsh conditions and Productions. It was commercially distributed by Univer- beaten, causing a severe brain-injury. A doctor recomsal Pictures theatrically, and by MCA Home Video for mends consulting a nearby specialist in order to best treat home media. Cry Freedom premiered in theaters nation- his injuries, but the police refuse due to fear that he might wide in the United States on 6 November 1987 grossing escape. (This would have been nearly impossible, consid$5,899,797 in domestic ticket receipts. The film was at ering that the severity of his injuries left him with nearly its widest release showing in 479 theaters nationwide. It complete inability to move on his own.) The security was generally met with positive critical reviews before its forces instead decide to take him to a prison hospital in Pretoria, around 700 miles away from Cape Town. He initial screening in cinemas. is thrown into the back of a prison van and driven on a bumpy road, aggravating his brain injury and resulting in his death. 1 Plot Woods then works to expose the police’s complicity in Biko’s death. He attempts to expose photographs of Biko’s body that contradicted police reports that he died of a hunger strike, but he is prevented just before boarding a plane to leave and informed that he is now banned, therefore not able to leave the country. Woods and his family are targeted in a campaign of harassment by the security police. He later decides to seek asylum in England to expose the corrupt and racist nature of the South African authorities. After a long trek, Woods is eventually able to escape to the country of Lesotho, disguised as a priest. His wife Wendy (Penelope Wilton) and their family later him, and are flown to Botswana with the aid of Bruce Haigh (John Hargreaves), a controversial Australian diplomat who uses his diplomatic immunity to help them. In the film, however, Hargreaves’ character is

Following a news story depicting the demolition of a slum in East London, South Africa, journalist Donald Woods (Kevin Kline) seeks more information about the incident and ventures off to meet black activist Steve Biko (Denzel Washington). Biko has been officially banned by the South African government and is not permitted to leave his defined banning area at King William’s Town. Woods is formally against Biko’s banning, but remains critical of his political views. Biko invites Woods to visit a black township to see the impoverished conditions and to witness the effect of the government-imposed restrictions, which make up the apartheid system. Woods begins to agree with Biko’s desire for a South Africa where blacks have the same opportunities and freedoms as those enjoyed by the white population. As Woods comes to un1

2

3

PRODUCTION

an Australian journalist.

• John Thaw - Jimmy Kruger, Minister of Justice

The film’s epilogue displays a graphic detailing a long list of anti-apartheid activists (including Biko), who died under suspicious circumstances while imprisoned by the government. Contrary to popular belief, the listing’s dates in the graphic actually stopped in June 1987, a few months before the film’s release, as the Apartheid government stopped releasing the increasingly obviously false “official explanations” for deaths in custody.

• Michael Turner - Judge Boshoff

2

Cast • Denzel Washington - Stephen Biko • Juanita Waterman - Ntsiki Biko, Steve Biko’s wife • Kevin Kline - Donald Woods

• Graeme Taylor - Dillon Woods, eldest son of Woods family • Kate Hardie - Jane Woods, eldest daughter of Woods family • Adam Stuart Walker - Duncan Woods, son of Donald and Wendy Woods • Hamish Stuart Walker - Gavin Woods, son of Donald and Wendy Woods • Spring Stuart Walker - Mary Woods, daughter of Donald and Wendy Woods • Munyaradzi Kanaventi - Samora Biko • George Lovell - Nkosinathi Biko

• Penelope Wilton - Wendy Woods • Kevin McNally - Ken, photographer at Daily Dispatch

3 Production

• Timothy West - Capt. de Wet

3.1 Development

• John Hargreaves - Bruce Haigh • Miles Anderson - Lemick • Morgan Sheppard as Policeman • Mawa Makondo - Jason • Wabei Slyolwe - Tenjy • Tommy Buson - Tami • Jim Findley - Peter Jones • Alec McCowen - British Acting High Commissioner • Zakes Mokae - Father Kani • John Matshikiza - Mapetla • Ian Richardson - State Prosecutor • • • • • • • •

Racial-demographic map of South Africa in the late 1970s.

The premise of Cry Freedom is based on the true story of Steve Biko, the charismatic South African Black Josette Simon - Dr. Mamphela Ramphele Consciousness Movement leader who attempts to bring Louis Mahoney - Lesotho Government Official awareness to the injustice of Apartheid; and Donald Woods, the liberal white editor of the Daily Dispatch Joseph Marcell - Moses, Lesotho postal worker newspaper who struggles to do the same after Biko is Sophie Mgcina - Evalina, Wood family’s domestic murdered. In 1972, Biko was one of the founders of the Black People’s Convention working on social upliftmaid ment projects around Durban.[2] The BPC brought toJohn Paul - Wendy’s Stepfather gether almost 70 different black consciousness groups and associations, such as the South African Student’s Gwen Watford - Wendy’s Mother Movement (SASM), which played a significant role in Nick Tate - Ritchie private aviator who took Woods the 1976 uprisings, and the Black Workers Project which ed black workers whose unions were not recogfamily from Lesotho to Botswana nized under the Apartheid regime.[2] Biko’s political acGarrick Hagon - McElrea, private aviator tivities eventually drew the attention of the South African

4.1

Critical response

government which often harassed, arrested, and detained him. These situations resulted in him being banned in 1973.[3] The banning restricted Biko from talking to more than one person a time, in an attempt to suppress the rising anti-apartheid political movement. Following a violation of his banning, Biko was arrested and later killed while in police custody. The circumstances leading to Biko’s death caused worldwide anger, as he became a martyr and symbol of black resistance.[2] As a result, the South African government banned a number of individuals (including Donald Woods) and organizations, especially those closely associated with Biko.[2] The United Nations Security Council responded swiftly to the killing by later imposing an arms embargo against South Africa.[2] After a period of routine harassment against his family by the authorities, as well as fearing for his life,[4] Woods fled the country after being placed under house arrest by the South African government.[4] Woods later wrote a book in 1978 entitled: Biko, exposing police complicity in his death.[3] That book, along with Woods’ autobiography Asking For Trouble, both being published in the UK, became the basis for the film.[3]

3.2

Filming

Principal filming took place primarily in the country of Zimbabwe due to the tense political situation in South Africa at the time of shooting. Other filming locations included Kenya, as well as film studios in Shepperton and Middlesex, England.[5] The film includes a dramatized depiction of the Soweto uprising which occurred on 16 June 1976. Indiscriminate firing by police, killed and injured hundreds of African school children during a protest march.[3]

3.3

Soundtrack

The original motion picture soundtrack for Cry Freedom was released by MCA Records on 25 October 1990.[6] It features songs composed by veteran musicians George Fenton, Jonas Gwangwa and Thuli Dumakude. At Biko’s funeral they sing the hymn Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika. Jonathan Bates edited the film’s music.[7]

4 4.1

Reception Critical response

Among mainstream critics in the U.S., the film received mostly positive reviews. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 81% of 21 sampled critics gave the film a positive review, with an average score of 6.4 out of 10.[8] Rita Kempley, writing in The Washington Post, said actor Washington gave a “zealous, Oscar-caliber performance as this African messiah, who was recognized as

3 one of South Africa’s major political voices when he was only 25.”[10] Also writing for The Washington Post, Desson Howe thought the film “could have reached further” and felt the story centering around Wood’s character was “its major flaw”. He saw director Attenborough’s aims as “more academic and political than dramatic”. Overall, he expressed his disappointment by exclaiming, “In a country busier than Chile with oppression, violence and subjugation, the story of Woods’ slow awakening is certainly not the most exciting, or revealing.”[11] Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times offered a mixed review calling it a “sincere and valuable movie” while also exclaiming, “Interesting things were happening, the performances were good and it is always absorbing to see how other people live.” But on a negative front, he noted how the film “promises to be an honest of the turmoil in South Africa but turns into a routine cliff-hanger about the editor’s flight across the border. It’s sort of a liberal yuppie version of that Disney movie where the brave East German family builds a hot-air balloon and floats to freedom.”[12] Janet Maslin writing in The New York Times saw the film as “bewildering at some points and ineffectual at others” but pointed out that “it isn't dull. Its frankly grandiose style is transporting in its way, as is the story itself, even in this watered-down form.” She also complimented the African scenery, noting that "Cry Freedom can also be ired for Ronnie Taylor’s picturesque cinematography”.[9] The Variety Staff, felt Washington did “a remarkable job of transforming himself into the articulate and mesmerizing black nationalist leader, whose refusal to keep silent led to his death in police custody and a subsequent coverup.” On Kline’s performance, they noticed how his “low-key screen presence served him well in his portrayal of the strong-willed but even-tempered journalist.”[13] Film critic Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film a thumbs up review calling it “fresh” and a “solid adventure” while commenting “its images do remain in the mind ... I ire this film very much.” He thought both Washington and Klines’ portrayals were “effective” and “quite good”.[14] Similarly, Michael Price writing in the Fort Worth Press viewed Cry Freedom as often “harrowing and naturalistic but ultimately selfimportant in its indictment of police-state politics.”[15] Mark Salisbury of TimeOut boasted on the film’s merits by declaring the lead acting to be “excellent” and the crowd scenes “astonishing”, while equally observing how the climax was “truly nerve-wracking”. He called it “an implacable work of authority and comion, Cry Freedom is political cinema at its best.”[16] James Sanford however, writing for the Kalamazoo Gazette, did not appreciate the film’s enduring qualities, calling it “a Hollywood whitewashing of a potentially explosive story.”[17] Rating the film with 3 Stars, critic Leonard Maltin wrote that the film was a “Sweeping and comionate film”. He did however note that the film “loses momentum as it spends too much time on Kline and his family’s escape

4

6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

from South Africa”. But in positive followup, he pointed out that it “cannily injects flashbacks of Biko to steer it back on course.”[18]

4.2

Accolades

The film was nominated and won several awards in 1987– 88.[19][20] Among awards won were from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Berlin International Film Festival and the Political Film Society.

4.3

Box office

6 Bibliography • Biko, Steve (1979). Steve Biko: Black Consciousness in South Africa; Biko’s Last Public Statement and Political Testament. Random House. ISBN 978-0394-72739-4. • Biko, Steve (2002). I Write What I Like: Selected Writings. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780-226-04897-0. • Clarke, Anthony J.; Fiddes, Paul S., eds. (2005). Flickering Images: Theology and Film in Dialogue. Regent’s Study Guides 12. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing. ISBN 1-57312-458-3.

The film premiered in cinemas on 6 November 1987 in limited release throughout the U.S.. During its opening weekend, the film opened in a distant 19th place and grossed $318,723 in business showing at 27 theaters.[28] The film Fatal Attraction opened in first place with $7,089,680 screening at 1,351 theaters.[1] The film’s revenue dropped by 10.6% in its second week of release, earning $284,853. For that particular weekend, the film fell to 25th place showing in 19 theaters. The film The Running Man, unseated Fatal Attraction to open in first place with $8,117,465 in box office revenue showing at 1,692 theaters.[1][28]

• Goodwin, June (1995). Heart of Whiteness: Afrikaners Face Black Rule In the New South Africa. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-81365-3.

Cry Freedom had one week in wider release beginning with the 19–21 February weekend in 1988.[1] The film opened in 14th place showing at 479 theaters grossing $802,235 in box office business. The film went on to top out domestically at $5,899,797 in total ticket sales through an 4-week theatrical run.[1] For 1987 as a whole, the film would cumulatively rank at a box office performance position of 103.[1]

• Magaziner, Daniel (2010). The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968-1977. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-08214-1918-2.

4.4

Home media

Following its cinematic release in theaters, the film was released in VHS video format on 5 May 1998.[29] The Region 1 Code widescreen edition of the film was released on DVD in the United States on 23 February 1999. Special features for the DVD include; production notes, cast and filmmakers bios, film highlights, web links, and the theatrical trailer.[30] Currently, there is no scheduled release date set for a future Blu-ray Disc version of the film, although it is available in other media formats such as Video on demand.[31]

5

See also • White savior narrative in film • 1987 in film

• Harlan, Judith (2000). Mamphela Ramphele. The Feminist Press at CUNY. ISBN 978-1-55861-2266. • Juckes, Tim (1995). Opposition in South Africa: The Leadership of Z. K. Matthews, Nelson Mandela, and Stephen Biko. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-27594811-5.

• Malan, Rian (2000). My Traitor’s Heart: A South African Exile Returns to Face His Country, His Tribe, and His Conscience. Grove Press. ISBN 978-08021-3684-8. • Omand, Roger (1989). Steve Biko and Apartheid (People & Issues). Hamish Hamilton Limited. ISBN 978-0-241-12640-0. • Paul, Samuel (2009). The Ubuntu God: Deconstructing a South African Narrative of Oppression. Pickwick Publications. ISBN 978-1-55635-510-3. • Pityana, Barney (1992). Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko & Black Consciousness. D. Philip. ISBN 978-1-85649-047-4. • Price, Linda (1992). Steve Biko (They Fought for Freedom). Maskew Miller Longman. ISBN 978-0636-01660-6. • Tutu, Desmond (1996). The Rainbow People of God. Image. ISBN 978-0-385-48374-2. • Van Wyk, Chris (2007). We Write What We Like: Celebrating Steve Biko. Wits University Press. ISBN 978-1-86814-464-8.

5 • Wa Thingo, Ngugi (2009). Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance. Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00946-6. • Wiwa, Ken (2001). In the Shadow of a Saint: A Son’s Journey to Understand His Father’s Legacy. Steerforth. ISBN 978-1-58642-025-3. • Woods, Donald (2004). Rainbow Nation Revisited: South Africa’s Decade of Democracy. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-233-00052-7.

7

[19] “Cry Freedom: Awards & Nominations”. MSN Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [20] “Cry Freedom (1987)". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 201006-15. [21] “Nominees & Winners for the 60th Academy Awards”. Oscars.org. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [22] “Cry Freedom”. BAFTA.org. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [23] “Cry Freedom”. Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [24] “Cry Freedom”. GoldenGlobes.org. Retrieved 2010-0615.

References

[1] “Cry Freedom”. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-0615. [2] “Stephen Bantu (Steve) Biko”. About.com. Retrieved 2010-06-20. [3] “Stephen Bantu Biko”. South African History Online. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[25] “31st Annual Grammy Award Highlights”. Grammy.com. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [26] “Awards for 1987”. nbrmp.org. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [27] “Previous Winners”. Political Film Society. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [28] “Cry Freedom”. The Numbers. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[4] 1978: Newspaper editor flees South Africa. BBC. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

[29] “Cry Freedom VHS Format”. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[5] Attenborough, Richard (Director). (1987). Cry Freedom [Motion picture]. United States: Universal Pictures.

[30] “Cry Freedom: On DVD”. MSN Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[6] “Cry Freedom: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack”. Amazon. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

[31] “Cry Freedom: VOD Format”. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-09-06.

[7] “Cry Freedom”. Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [8] Cry Freedom (1987). Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [9] Maslin, Janet (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [10] Kempley, Rita (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [11] Howe, Desson (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [12] Ebert, Roger (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [13] Variety Staff (1 January 1987). Cry Freedom. Variety. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [14] Siskel, Gene (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. At the Movies. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [15] Price, Michael (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Fort Worth Press. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [16] Salisbury, Mark (6 November 1987). TimeOut. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

Cry Freedom.

[17] Sanford, James (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Kalamazoo Gazette. Retrieved 2010-06-15. [18] Maltin, Leonard (5 August 2008). Leonard Maltin’s 2009 Movie Guide. Signet. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

8 External links • Official website • Cry Freedom at the Internet Movie Database • Cry Freedom at AllMovie • Cry Freedom at the Movie Review Query Engine • Cry Freedom at Rotten Tomatoes • Cry Freedom at Box Office Mojo • Cry Freedom film trailer at YouTube

6

9 TEXT AND IMAGE SOURCES, CONTRIBUTORS, AND LICENSES

9

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

9.1

Text

• Cry Freedom Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cry%20Freedom?oldid=638815586 Contributors: Deb, SimonP, Skysmith, Dimadick, Academic Challenger, David Gerard, Angmering, Andycjp, Lockeownzj00, Robert Brockway, OwenBlacker, Kuralyov, ScottyBoy900Q, Jayjg, Discospinster, WegianWarrior, Darwinek, Erik, Cburnett, Panchurret, Kelisi, GregorB, Rjwilmsi, Harro5, Darguz Parsilvan, MarnetteD, Andreas S., Jay-W, Gwernol, YurikBot, RussBot, Briaboru, Quentin Smith, Muntuwandi, UDScott, Catamorphism, RFBailey, Bigrich, Bibliomaniac15, SmackBot, Pgk, Michaelbeckham, Kintetsubuffalo, Jakz34, Bluebot, Zaian, Dr.Poison, JJW20084, Halaqah, Xionbox, Dl2000, Benmay, Luigibob, Aapold, Lbr123, CmdrObot, ShelfSkewed, Cydebot, Treybien, Tec15, Alaibot, Gnfnrf, NorthernThunder, BetacommandBot, Thijs!bot, Marek69, Dawkeye, ABCxyz, MegX, Joshua, Easchiff, PacificBoy, Avicennasis, Indon, Emcardi, Grushenka, Mannerheim, Blupping, MartinBot, Rhino131, Wlodzimierz, Mike.lifeguard, PythonMonty504, Jojoster, Tai kit, Themoodyblue, Crazytrucker, Sparkymeg, Philip Trueman, OldZombie, Broadbot, McM.bot, Sparkling Gray, Pällikkä, SieBot, Nubiatech, A. Carty, Aspects, Beemer69, ClueBot, The Thing That Should Not Be, Jan1nad, RossMcG, Justinmckee07, HarryKG, GDibyendu, Addbot, EjsBot, Tide rolls, Zorrobot, Luckas-bot, Yobot, AnomieBOT, Ulric1313, Materialscientist, LilHelpa, Xqbot, Tuesdaily, Ched, LucienBOT, Nakakapagpabagabag, Winterst, ScottMHoward, Cnwilliams, Hummingbird347, Nistra, EmausBot, Wikipelli, ZéroBot, Josve05a, DeWaine, SporkBot, Δ, ClueBot NG, Helpful Pixie Bot, Montalban, Katangais, MinghamSmith, Mmancino, JustBerry, Dancedom, Taylor Trescott, Vieque and Anonymous: 135

9.2

Images

• File:South_Africa_racial_map,_1979.gif Source: http://.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d1/South_Africa_racial_map% 2C_1979.gif License: Public domain Contributors: Transferred from en.wikipedia; transferred to Commons by :Magnus Manske using CommonsHelper. (Original text : * Site: Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection: South Africa Maps Original artist: U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Original er was MaGioZal at en.wikipedia • File:Video-x-generic.svg Source: http://.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/e/e7/Video-x-generic.svg License: Public domain Contributors: ? Original artist: ? • File:Wikiquote-logo.svg Source: http://.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fa/Wikiquote-logo.svg License: Public domain Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

9.3

Content license

• Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0